A couple of weeks ago, a security announcement (CVE-2014-0160) was made regarding a simple buffer over-read bug in a library.

This library is OpenSSL.

OpenSSL, for those who don’t know, is the library which deals with the encryption on the web (so stuff like https). A buffer over-read is something like this – let’s say I have a variable with three letters in it:

Hi!

What you don’t see is that this is stored in the middle of memory, so it’s actually surrounded by a load of other stuff:

sdflkjasHi!kldjlsd

With non-simple variables, such as blocks of text (character strings), a computer doesn’t directly know how big it is. It is up to the programmer to keep track of this when the variable is created. This allows a programmer to read back from memory a larger amount of data than is actually stored. This is almost always a bug, as the data that’s past the end is usually meaningless, and possibly dangerous depending on what is done with it.

If I was to read 5 letters from my 3 letter variable, I’d get this:

Hi!kl

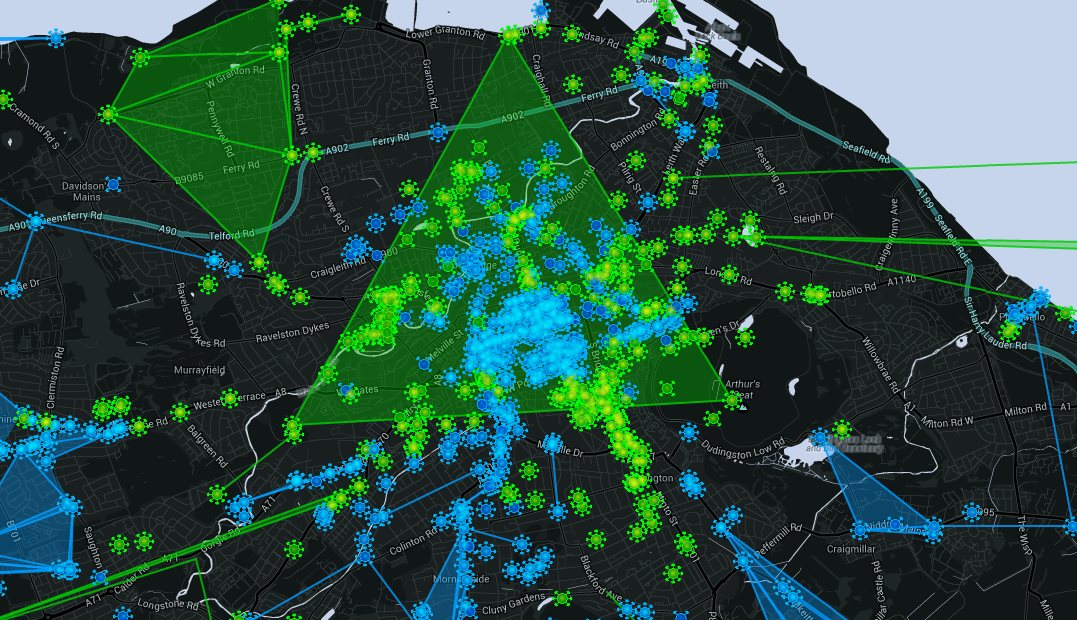

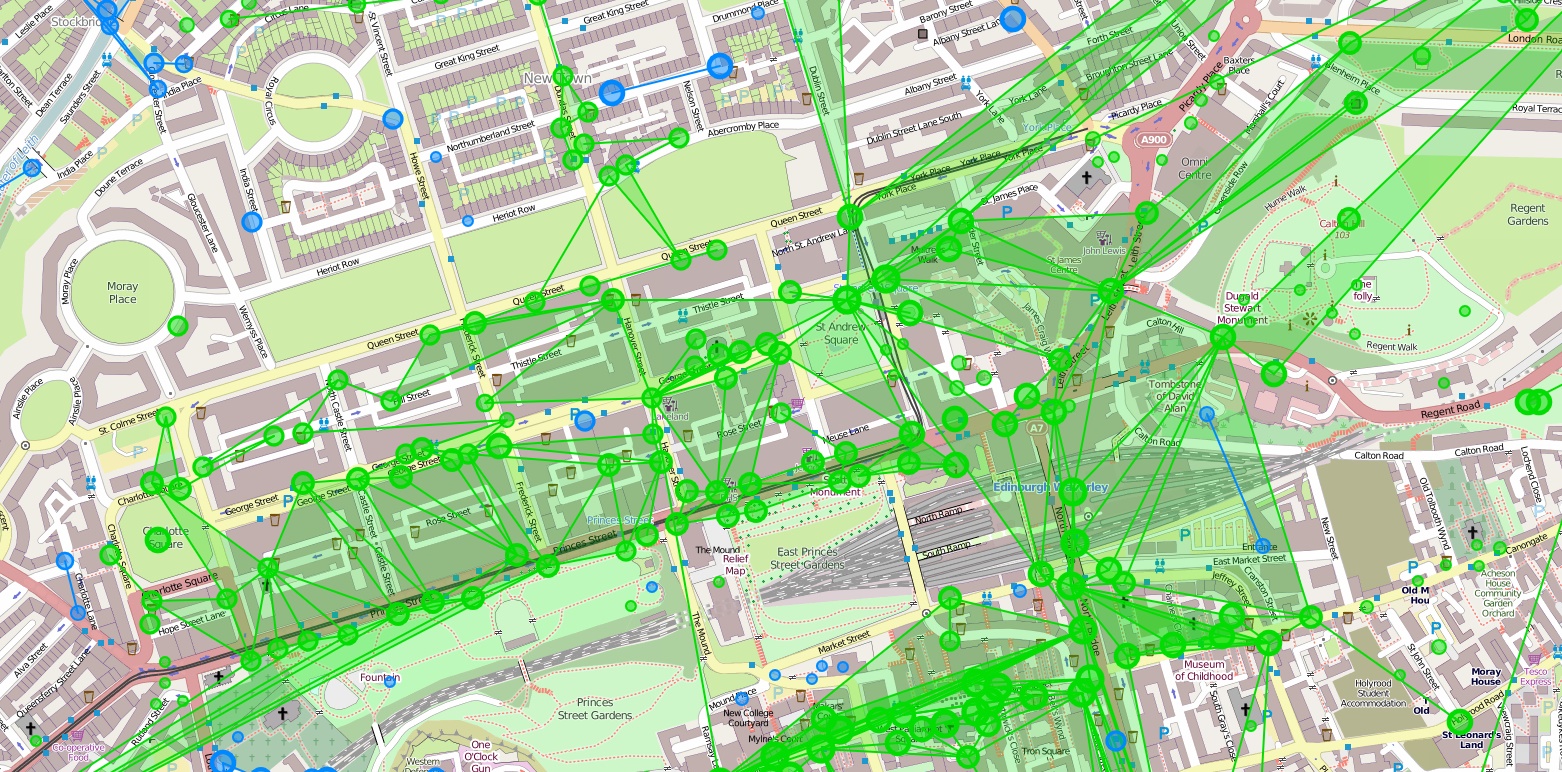

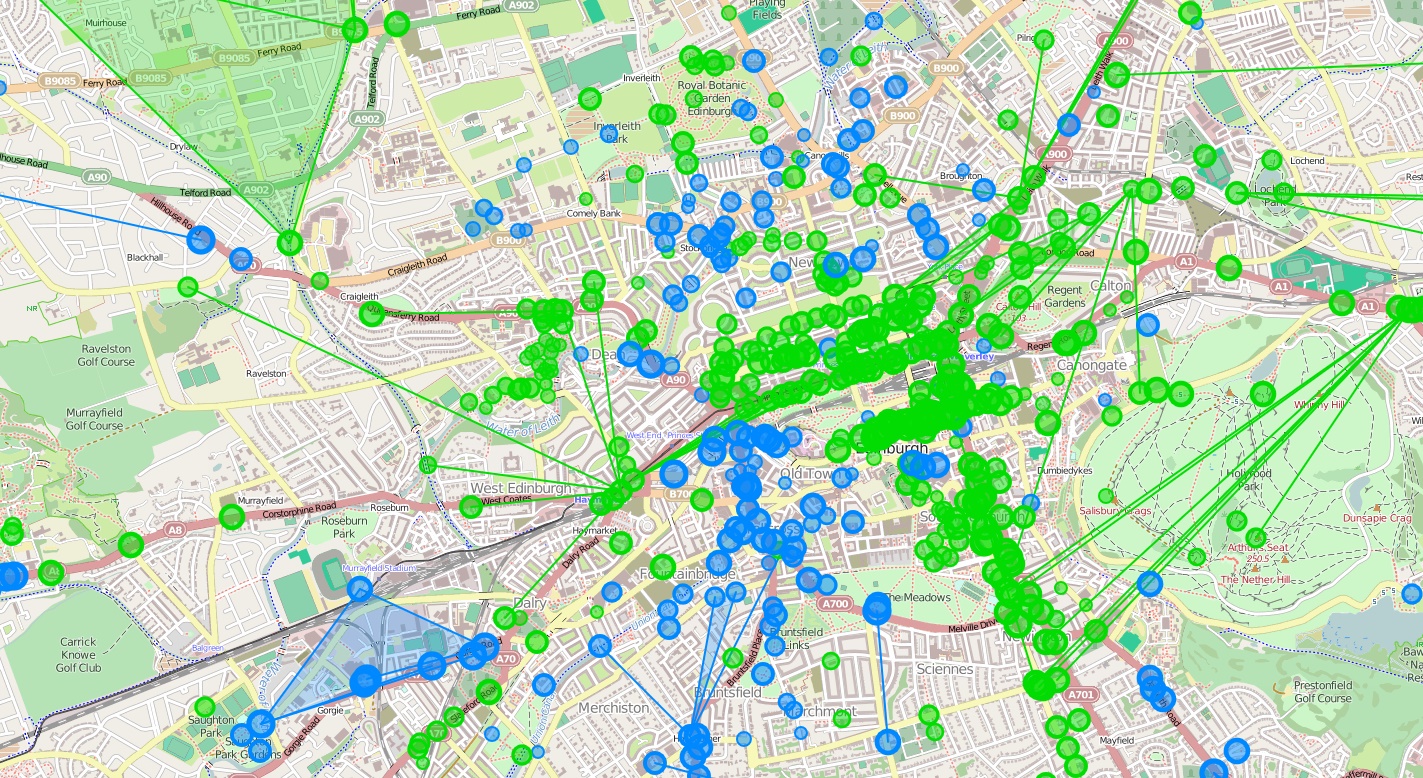

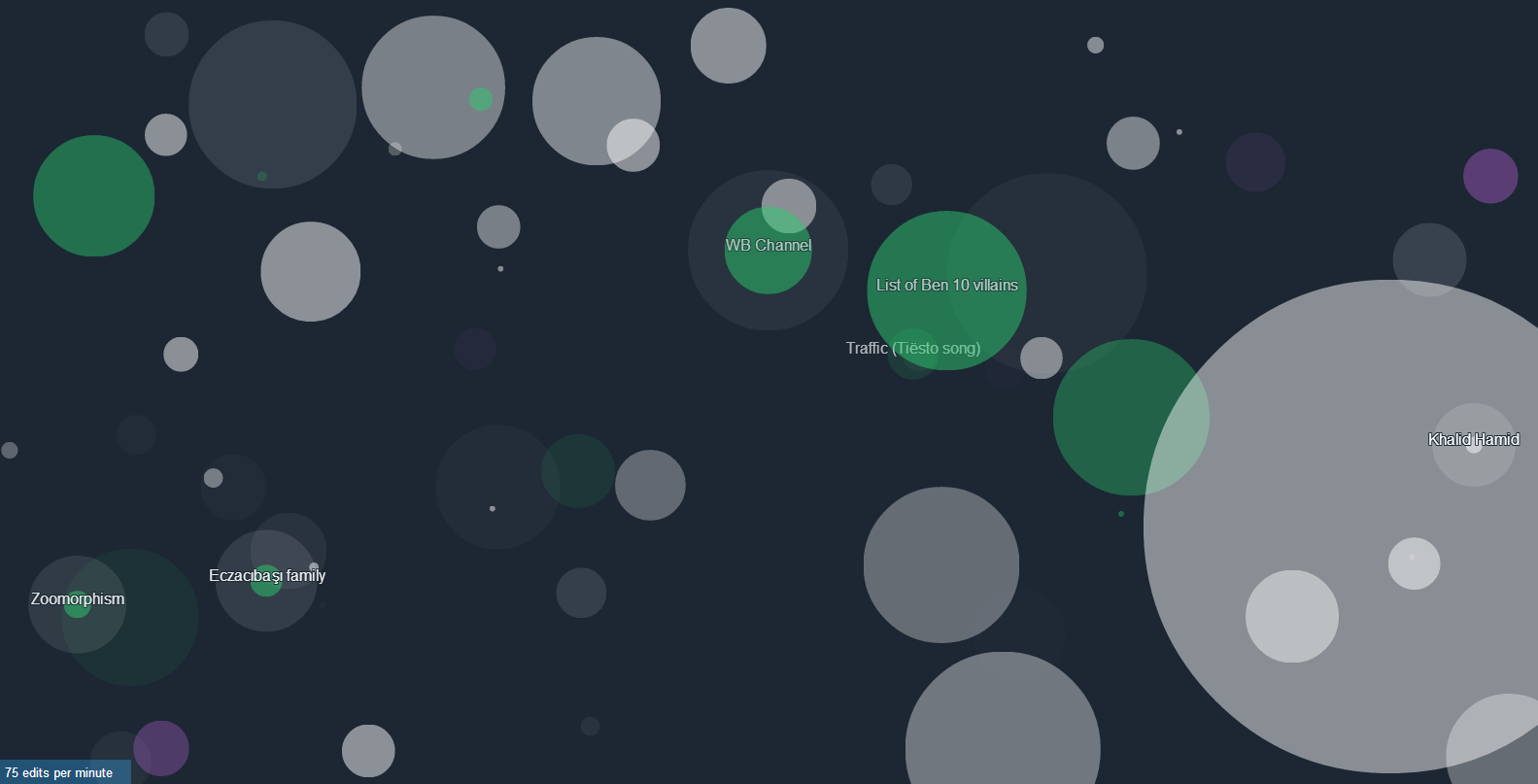

What actually happened with Heartbleed was something very similar. Part of the protocol allows the one end to send a “heartbeat” to keep the connection alive. Part of this request allows the sender to specify some data to be returned back to them. As the server doesn’t know how long this is, you have to tell it too. xkcd has a really good explanation of this in comic form:

Of course, being able to read random bytes from a process’ memory is a bit of an issue for security, as there is usually some data in that memory that you don’t want the user to know. In a multi-user environment, this normally comes in the form of private data about other users. It’s a pretty serious security vulnerability on it’s own. However, this isn’t just any application, it’s OpenSSL – a widely-used public key encryption library.

Public Key Encryption

For those who don’t know what public key encryption is, here’s a quick primer.

If I want to protect some data when I send it to you, I would encrypt it. With classical encryption, I would create some key which we both have or know, and use that to encrypt the data, then I could be confident that it’s not going to be intercepted en-route to you. This does mean that I need to use a different key for everybody I send data to, and need a secure way of exchanging this data with everyone, which could cause a lot of issues.

Public key encryption solves this by creating a “key pair”, composed of a “private” key and a “public” key. Some complicated mathematical operation and relationship between these two keys means that the public key can be used to encrypt data, and then only the private key can be used to decrypt that data. The relationship between the keys means that the private key can never be derived from the public key, so you can freely distribute, publish, and shout from the hilltops your public key. Then, anyone who wants to get in contact with you can take your public key, and encrypt the data, and then only you could decrypt it.

Public key encryption is the base for SSL (secure sockets layer), which itself is the base for HTTPS.

Certificates, and Heartbleed

The public keys used for HTTPS are the certificates that your browser shows. Combined with the server’s private key, communication between the server and the browser can be completely encrypted, protecting the transmitted data.

The Heartbleed bug, however, allows any client to request about 64KiB of memory from the server, and to perform the encryption, this memory has to include the server’s private key. If the client is lucky, then they can download the private key (or the set of large prime numbers that make it) of the server and reconstruct the encryption keys locally.

Consequences of leaked private keys

There are quite a few consequences of a private key being leaked, especially when it’s been signed by a trusted third party (like almost all SSL certificates are signed by a CA). The obvious one is that any traffic you encrypt with this public key is now readable by anyone with the private key. Think along the lines of passwords, credit card numbers, etc.

What isn’t immediately thought of is the fact it’s possible to decrypt this data offline – if an attacker had saved your encrypted traffic from years ago, it’s possible that they could now decrypt that traffic. Implementing forward secrecy would go some way to mitigate this.

If the compromised credentials aren’t revoked (or the user doesn’t check revocation lists – the default in Google Chrome), then the attacker can then use those credentials to perform a future man-in-the-middle attack, and intercept any future data you send to a site.

Basically, if someone gets hold of that private key, you’re in trouble. Big trouble.

Recovery

By now, you should have updated to the fixed versions of OpenSSL, and made sure any services using the libraries have been restarted to apply the change.

You should also assume the worst-case scenario – private key data has been fully compromised, and is in the wild. Certificates should be revoked and re-issued BEFORE any other changes of secure credentials, otherwise the new credentials could also be leaked.

Anything that has the potential to cause adverse effects if exposed should be invalidated. This includes credentials like passwords, security keys, API keys, possibly even things like credit card numbers. From a security standpoint, this is the only way you can be completely safe from a leak due to this bug. From a reality standpoint, most people won’t be affected, and stuff like credit cards don’t need to be replaced, just keep a really close eye on statements and consult your bank the moment you notice something amiss.

Now would also be a really good time to start using password manager software like KeePass, so you can use strong and unique passwords for every service without worrying about remembering them all. KeePass uses an encrypted container with a single password (or key file, or both) that protects all the data stored within it.

The future

The bug is a simple missing bounds check. It’s the sort of bug that gets introduced thousands of times a day, and fixed thousands of times a day. Sometimes one or two slip through the gaps. Usually, they’re in non-security-critical code, so any exploitation of these doesn’t give an attacker much to work with.

Sometimes, just sometimes, one of these gets it’s way into a critical bit of code. Sometimes, this then gets released and isn’t spotted for a while. Who’s fault is it? Well, it’s really hard for a developer to see mistakes in their own code. That’s why we have code review. Not every bug is going to be seen by everyone at review stage. Nobody can reasonably assign blame here, and that’s probably not even the right thinking for this.

We should be looking at how we can reduce the frequency of events like this. For starters, this should be added to code review checklists (if it’s not there already!). OpenSSL should also add regression checks to make sure that the same bug isn’t introduced again.

It should be a global learning experience, not a situation where everyone points fingers.

OpenSSL is open-source software – the source code is freely available for anyone to view and edit. Anyone can review the code for security holes, and the developers have a disclaimer which states they supply the software “as-is”, so it’s the responsibility of the users of the software to make sure it works as expected. Open-source software is meant to be more secure because anyone can review it for security holes, but in practice I feel this rarely happens.

Let’s work together – the entire internet community – to make the internet a safer and more secure place. We have done really well with things like SSL, but bugs like this have seriously dented confidence in the security of the internet. Let’s work together to rebuild that trust to a level beyond what it was at before.

This site

This site, and the other sites hosted on this server were amongst the many thousands of other websites which have been hit by this bug. While there’s no indication that the bug was ever exploited, I cannot guarantee that it’s not been. Consequently, I’ve done the thing that so many other sites have done, and patched the hole, and reissued credentials and certificates as necessary.